A Brief History of the Hall Family

Taken from the book Finding Margaret by John Hussey. Published 2011 by Countrywise Ltd. Copyright John Hussey.

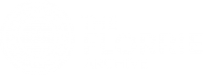

Bernard Hall was the tenth of ten children, born in Cheadle, Staffordshire in 1813, six years after the abolition of the slave trade.

George III was still King of England until 1820 when he was succeeded by George IV followed by William IV. By the age of 24 Bernard Hall had seen three monarchs come and go before Victoria ascended to the throne in 1837.

Bernard moved to Liverpool as a young man to take over the family business, a West Indian Merchant Company set up by his father John Hall. In 1843 he married his cousin Anne Titley at St Catherine’s church that once stood on the corner of Grove Street and Oxford Street before being destroyed by a German bomb during the 2nd World War.

Bernard and Anne lived in 26 Catherine Street and went on to have four children, William, Bernard, Emilia and Alexander. Wealth and privilege were no immunity against the high mortality rates in children in Victorian England and sadly both William and Emilia died in infancy.

In 1849 Bernard threw his hat into the ring of local politics and was elected Conservative Councillor for Abercromby Ward. He lost his seat three years later, defeated by Mr Robertson Gladstone. In 1854 Bernard contested North Toxteth Ward and was returned by a mere 7 votes, defeating W.H. Ogden.

The stark contrast between Bernard Hall’s way of life and that of the inhabitants of Toxteth was a vast chasm both in class and culture and there’s no doubt that his tenure among an underclass which was largely poverty-stricken would have been both a culture shock and a learning curve; its quiet clear the Bernard acquired a fondness for his constituents and his several years among the people of Toxteth greatly influenced his thinking. The plight of the poor did not leave him unmoved and he attempted to alleviate that poverty in his own distinctive way. Three years after his election victory in 1857, his wife died at the age of 34 and Bernard did not seek re-election at the end of his term or attempt to re-enter politics for many years afterwards.

Left a widower with small children, in 1860 at the age of 44 he was married again to Margaret Calrow and the family moved to the suburb of Wavertree at Ludlow House, which still stands today.

And so, for the second time, Bernard began family life anew, he went on to raise a further six children; Percy, Margaret, Florence, Douglas, Evelyn and Muriel. Just as it was with his first wife, the shocking chid mortality rates was increased further when Evelyn died at three years of age.

Bernard Hall: The First Mayor of Liverpool

In 1879 Bernard Hall was elected Mayor of Liverpool; the appointment of mayor was a prestigious honour at any time but as things turned out, Bernard’s tenure was to prove more auspicious than most. It was an unforeseen circumstance that Bernard’s year of office coincided with Liverpool’s official elevation to the status of “City” and it could be said that Bernard Hall was the first Mayor of the City of Liverpool.

In any account of Bernard Hall, there is always a mention of his benevolence and generosity towards those in need and on the occasion of a new Irish famine in the winter of January 1880, he lent his considerable civic weight into helping William Simpson raise money for famine relief.

A Royal Visit

On the 22nd January 1880, Princess Louise, the Marchioness of Lorne and Queen Victoria’s sixth child, was to join her ship the Samaritan, leaving from Liverpool. Crowds gathered at Lime Street station to await her arrival, accompanied by the Duke of Edinburgh and The Prince of Wales. On the train’s arrival the Princess was greeted by the Mayor and Mayoress and presented with a bouquet of flowers by a young lady of the Mayor’s family – it is not stated which young lady but it was probably Florence. Princess Louise returned to Liverpool in 1906, when she unveiled the statue of Queen Victoria in Derby Square.

Philanthropy

Bernard Hall had for many years taken a great interest in promoting education throughout the city and had initially donated the sum of £500 to found a scholarship which lasted many years; it is only in retrospect that it can be seen that within this incipient philanthropy lay the seeds of what would later be his finest legacy to the City. Although his name is rarely mentioned in the founding of Liverpool University, he was ever-present in chairing those meetings which eventually culminated in the creation of what was then called University College, with an initial grant from Liverpool City Council of the astronomical sum of £80,000! Liverpool University admitted its first students in 1882.

Bernard Hall’s charitable donations to the City are often understated but his name crops up regularly as a funder of educational works. Not least among them the Bluecoat School, where he takes his place among luminaries Brian Blunder, Thomas Ismay, David Lewis and Sir Andrew Barclay Walker.

In his later years he endured failing health and retired from public life in 1883. He spent his days at Nice and Cannes, where he built a magnificent house, Mariposa (Spanish for butterfly). However, Mariposa was not, as he thought, his final bow; he would soon be building a different type of monument altogether, in a far less salubrious setting than the French Riviera. The event of his daughter Florence’s tragic death on 5th June 1887 brought Bernard back to public life & inspired possibly the most significant act of philanthropy of his career: the building of The Florence Institute.

Florence Bernadine Hall: 1865-1887

Born in 1865 Florence Bernadine Hall was the third child of Bernard Hall and Margaret Carlow his second wife and one of ten children in total. Born in Dudlow House, a grand mansion in Wavertree Liverpool.

There is very little information about Florence’s life, but there are some factual events in which we believe Florence was present, for example, in 1880 The Duke of Edinburgh, The Prince of Wales and a young Princess Louise arrived in Liverpool to join Queen Victorias ship The Samaritan, leaving from Liverpool docks. On arrival at Lime Street Station the Royal party were greeted by Bernard Hall as the Mayor of Liverpool and presented with a bouquet of flowers by a young lady of the Mayors family. Florence would have been fifteen years old at the time of this Royal visit but is likely to be Florence.

In later years we know Florence followed her older sister Margaret Hall to Paris, as an art student. Margaret herself was on the cusp of a promising career as an artist when Florence died. Margaret’s famous work includes the depiction of Fantine from Victor Hugo’s novel, Les Miserables, which hangs in the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

Unfortunately we can not find any records of how Florence died, although there has been a suggestion she died of cholera. It is estimated the fifth cholera pandemic between 1883-1887 claimed 250,000 lives in Europe.

Bernard Hall was 74 years old at the time of Florence’s death, which rocked the Hall family to the core. The tragedy of his daughters death spurred Bernard into a final flurry of philanthropic creativity, a fitting memorial to his daughter.

The Florence Institute was a finer choice of memorial to Florence Bernadine Hall than any ornate sepulchre and has succeeded in preserving her name ad infinitum, affectionately recalled by generations of young people who have always been an integral part of the building.

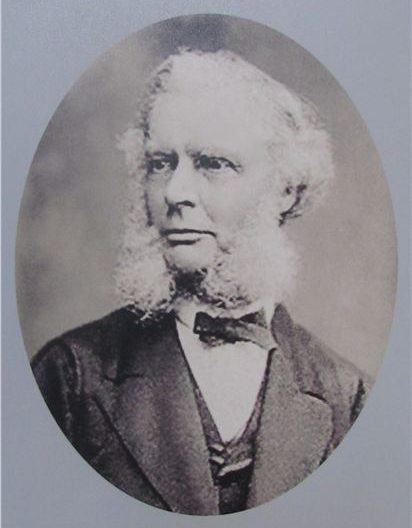

The architectural excellence of the Florence Institute remains a reflection of Bernard Hall’s love for his daughter. Placed upon the wall of the Florence Institute is a white marble, bas-relief of Florence with the wording beneath;

“This building was erected in the year 1889 by Bernard Hall, West Indian Merchant and once Mayor of this city, in memory of his daughter Florence who died in Paris in the year 1887 aged 22 in the hope that it might prove an acceptable place of recreation and instruction for the poor and working boys of this district of the city”

There is reason to believe that Florence’s older sister Margaret Hall herself designed the plaque, although it was sculpted by Francis John Williamson (1833-1920) a favourite of Queen Victoria. The plaque is dated “1890, Esher” which indicates that it was sculpted in Williamson’s studio in Esher, Surrey and erected at the Florence Institute in 1890, one year after opening and where it still remains today.

Architects

The Florence Institute for Boys was built with Bernard Hall’s own money, a costly sum in the region of £15,000, which equates to a staggering £1.3 million in today’s money.

Cornelius Sherlock was the chosen architect for the building and the ornate doors, ornamental balconies, curved stonework and central tower facing the river are typical of his work. Cornelius Sherlock left a rich legacy of buildings around Liverpool, from No.1 Victoria Street, built for Sir Andrew Barclay Walker, to St. Steven’s Church, Gateacre and the unmistakable frontage of the Walker Art Gallery and Picton Library with their distinctive Corinthian pillars.

Unfortunately Sherlock died a year before the opening of the Florence Institute and the building was completed by Herbert Keef. The interior of the building was completely given over to “the provision of recreation of an innocent and healthful kind for working boys at the critical period of life between the time they leave school and enter upon their manhood”.

The Florence Institute Opens

The Florence Institute was officially opened on Saturday 7th September 1889, and the great and the good of the city gathered at the invitation of Mr and Mrs Bernard Hall. Sadly, Bernard Hall was too unwell to attend the ceremony which was instead attended by his extended family. Also in attendance were the Lord Mayor Ernest Cookson, Edward Whitley MP, Sir David Radcliffe and F.W. Lowndes.

The first Annual Meeting of the Florence Institute was held on 23rd October 1890 at Liverpool Town Hall. Within its first year, described by the Committee as ‘experimental’, it was placed on record that 600 boys had attended the Institute.

Florence Bernadine Hall: A Final Resting Place

In the churchyard of All Saints Church, Childwall are two headstones of significant importance in the history of The Florence Institute. The first is a simple cross, placed in the grass without a single word to denote who it memorialises. The headstone is that of Florence Institute architect Cornelius Sherlock.

The second headstone is placed at the vault of the Hall family, in poor condition, with much of the leaded lettering missing, and a cross that needs fixing back into place. This is the final resting place of siblings Margaret Bernadine Hall, Bernard Vincent Hall, Evelyn Bernadine Hall and Florence Bernadine Hall.

THE FLORENCE INSTITUTE

- 01517282323

- info@theflorrie.org

377 Mill Street, L8 4RF

We are open:

9am – 6pm Monday, Wednesday & Friday.

9am – 9pm Tuesday.

Registered Office: The Florence Institute Trust Ltd, 377 Mill Street, Liverpool L8 4RF. Charity Registration No: 1109301. Company Registration No: 05330850 (registered in England and Wales).